The Eleventh Ingredient

First published in THE JERUSALEM REPORT July 2, 2001

For two millennia, scholars have argued over the formula for the mystical incense that burned in the Temple. Now, a local aromatherapist claims he is about to replicate it.

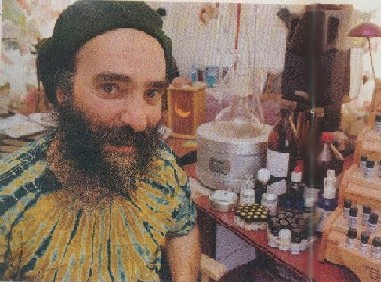

Avraham Sand stands behind a lectern in the corner of the room that serves as his office, on the top story of his moshav house in Mevo Modi’im, the village of late folk-rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. He reads aloud from a massive siddur which rests between small bundles of dried-out herbs and plant stems. In neat rows on the shelves behind him stand vials of essential Oils, labeled with the names of plants from all over the world.

Pointing to each word with his finger, Sand enunciates a Hebrew passage from Exodus (30:34-36) that lists each ingredient in ketoret besamim, the incense that was burned each day when the cohanim, the priests of the First and Second Temples, made sacrifices to God. The reading over, Sand, his eyes tearing up with emotion, describes the holiness and the power of the ancient concoction, a long-lost scent comprising 11 ingredients, which he has spent the past 15 years trying to replicate. Now, at last, he says, he’s ready to unlock the secret of the Temple fragrance.

The “rediscovered” scent, he says in hushed tones, will “lift people beyond their rational mind, directly to their intuitive mind. It will take us back to the days of the Temple, and stimulate us to re-elevate ourselves and rebuild the Temple.”

A businessman trading in rare fragrances, Sand has been commuting between Mevo Modi’im and his native Oregon for 20 years. An aromatherapist by training, he’s been recreating the ketoret scent in partnership with Reuven Prager, an entrepreneur and salesman originally from Miami, who mints coins and replicates Temple-era clothing, and shares Sand’s enthusiasm for the rebuilding of the Temple. (Asked how this rebuilding could be reconciled with the presence on the mount of the alAqsa mosque and the Dome of the Rock, Prager replies: “I do not see the mosques as an obstacle. If it is God’s will to bring about the situation, the Moslems will dance those mosques off the Temple Mount in the spirit of God’s will.”)

Their 15-year quest for the magical scent has involved piecing together clues found in the cave of Qumran, analyzing oils from commercial flower plantations in India, and gathering bits of snail shell from California fisheries. And the result, very soon Sand hopes, will be a vial of oil identical in scent to the Temple incense.

According to Talmudic legend, members of the House of Avitnas, who lived on the Temple Mount, were the sole guardians of the formula of the aroma, which Jewish mystics say could raise an ordinary person to the spiritual level of prophecy, capable, says Sand, “of seeing from one side of the earth to the other.” But after the destruction of the Second Temple, the story goes, that recipe was lost.

Four of the 11 spices are named in Exodus (and commonly translated as balsam, clove, galbanum and pure frankincense). The other seven (usually translated as myrrh, cassia, spikenard, saffron, costus, aromatic bark and cinnamon), and the relative proportions, are discussed in the Talmud.

The problem is that no one knows exactly what the Avitnas clan did to each of the raw materials, to blend them into a completed scent. Nor, indeed, has there been any consensus as to precisely which substance each of the Hebrew names describes. Scholars over the centuries, from famous names like Gamliel and Maimonides to enigmatic Rabbi Natan of Babylon, have argued these questions. Most troubling of all has been the true identity of the “clove”-or tziporen.

But until recently, all the learned argument was academic, because of a specific Biblical prohibition against replicating the incense for non-Temple use: “Whoever makes it shall be cut off from his kin,” Exodus 30:37 states. In 1985, however, Prager thought he had found a loophole, and Rabbi Menachem Burstein, an authority on Temple-period botany and chemistry who runs the Shlomo College of Temple studies (and a Jerusalem infertility clinic), agreed with him: The ban need not apply, if the ingredients are steamed to extract their Essential Oils, rather than ground into a powder as a prohibited spice.

Sand got to work. But by 1992, he had still managed to produce only seven of the 11 oils. Then came a breakthrough: Vendyl Jones-the American Baptist pastor-turned-archaeologist who claims to be the inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s movie hero Indiana Jones-discovered an underground container filled with 600 kilos of strange red material at a cave near Qumran, by the Dead Sea.

Jones, who was ejected from the site when his Israel Antiquities Authority digging license expired, published a chemical analysis of the red powder-to support his claim that it was none other than the secret Temple incense. Using that analysis, with what he calls “fair certainty,” Sand moved from seven ingredients to 10.

It was an emotional moment for him and Prager. “I rubbed the oil into my beard and pe’ot [sidelocks], Prager recalls, in an interview at his apartment/office in Jerusalem. “I ran to the Kotel [Western Wall] as fast as I could. I wiped my face across the stones of the Wall, and whispered to them ‘Do you remember-do you remember this smell?'”

BUT WHILE SAND HAD 10 INGREDIENTS, he was still stumped by the tziporen. And he remained stumped until he came upon Prof. Zohar Amar, of the land of Israel Studies Department at Bar-Ilan University, author of a recent pamphlet on the specific subject of that mystery ingredient, and of a forthcoming book on the incense. Cloves are a nonstarter, Amar has ruled. “They only came to this region in the Middle Ages,” a millennium after the destruction of the Second Temple, he told The Report.

BUT WHILE SAND HAD 10 INGREDIENTS, he was still stumped by the tziporen. And he remained stumped until he came upon Prof. Zohar Amar, of the land of Israel Studies Department at Bar-Ilan University, author of a recent pamphlet on the specific subject of that mystery ingredient, and of a forthcoming book on the incense. Cloves are a nonstarter, Amar has ruled. “They only came to this region in the Middle Ages,” a millennium after the destruction of the Second Temple, he told The Report.

Instead, Amar has now identified tziporen as the “operculum”-the fingernail-shaped trap-door at the entrance to the shell of a sea snail. Improbable though this may sound, the opercula of sea snails-in English referred to as “Devil’s Claw”-have in fact been ground down and used as a fragrance since ancient times. Indeed, Amar has established, such a fragrance is still for sale in the bazaars of Turkey today. (This isn’t the first time that modern scholars have posited the use of snail content in ritual concoctions: For almost a decade, P’til Tekhelet, a Jerusalem-area company, has been producing the blue dye prescribed in the Bible for one thread of the tzitzit, using an extract from the gland of the murex trunculus, a snail indigenous to the northern Israeli coastline.)

Relying on ancient Greek and Latin texts, Amar has narrowed the search from the tziporen to two species of sea snail found in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, Murex anguliferus and Strombus lentiginosus.

Using clove rather than the snail-shell extract, Sand has already blended together a sample mix of all 11 fragrances. A transparent oil, it initially smells like a rather exotic furniture polish, but the scent is truly subtle, its ingredients gradually making themselves apparent, and its deeper, intricate mixture of fragrances tingles in the nose for some time.

Now he’s waiting anxiously for the “genuine” eleventh ingredient-although he and Prager are cagey as to whether they’ll manufacture the final product in commercial quantities. Sand stresses that, because he is producing an oil rather than the incense, the concoction will not bestow prophetic powers on those who smell it. But he does emphasize, and there’s the passion of a 15-year quest in his eyes as he says this, that he does believe the scent will boost the effort to rebuild the Temple.